Efforts at the state and local levels

Advocates around the country, many of whom have been working on policing issues for decades, have engaged in tireless efforts to help transform our public safety system while limiting the scope of policing. A wave of policing-related bills and policies were introduced in the recent past, and in state legislatures alone, 3,000 policing related bills were introduced in response to protests in the summer of 2020.

For a comprehensive overview of legislation that enhances policing accountability, reduces the scope of policing, and invests in Black and Brown communities, visit here.

A number of community members and organizations have also pushed to shift the role of existing law enforcement agencies. For example, in Minneapolis, a ballot measure was proposed to eliminate the police department and replace it with a Department of Public Safety, which would take a public health centered approach to public safety matters.

State and local government efforts to address police accountability have begun to include investigations by state Attorneys General who now have authority in eight states (California, Colorado, Massachusetts, Nevada, New York, Oregon, Virginia, and Washington) to conduct investigations into law enforcement agencies that have shown a pattern-or-practice of unlawful conduct. Examples include the California Attorney General’s probe into the Santa Clarita County Sheriff’s office and the Colorado Attorney General’s pattern and practice investigation into the Aurora Police Department which resulted in a consent decree in 2021.

Efforts at the federal level

The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) has the power to investigate local and state law enforcement agencies for patterns or practices of unconstitutional conduct. After numerous police-involved shooting deaths of unarmed persons of color in cities, communities have asked the DOJ to open federal investigations of their local police departments. In some cities, the Civil Rights Division of DOJ has responded by conducting a civil rights probe of a law enforcement agency. LDF encourages community activists to consider the differences between these investigations and other accountability or advocacy efforts to determine which approach best meets the needs of their communities.

Federal legislation has also been introduced to address expansive police protections as well deficiencies in our criminal-legal system and public safety apparatuses. This legislation includes the Ending Qualified Immunity Act that moves to abolish qualified immunity, a federal judicial doctrine which allows law enforcement to escape civil liability for their misconduct. Others include the Marijuana Opportunity Reinvestment and Expungement (MORE) Act, which would end the criminalization of marijuana at the federal level, and The People’s Response Act, which promotes investments in community-based services to reduce criminalization and promote community safety. Previously, the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, which contained critical provisions including abolishing qualified immunity, passed twice in the U.S. House of Representatives before stalling in the Senate.

Private lawsuits

Private lawsuits have been filed against police departments to address abusive practices. In Floyd et al. v. City of New York, a federal judge found the New York Police Department (NYPD) liable for a pattern and practice of racial profiling and unconstitutional stops. A federal judge is currently monitoring the NYPD’s implementation of court-ordered reforms to address biased policing practices. Information about the reform process is available here. In Davis v. City of New York, a case litigated by LDF, the court found that the NYPD stopped and arrested people of color who lived in or visited public housing apartments, without reasonable suspicion or probable cause. In 2015, the court approved a settlement to remedy the NYPD’s unlawful practices in public housing.

When the Trump administration created the President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and the Administration of Justice to, in part, promote “public respect for the law and law enforcement,” composed almost entirely of law enforcement, LDF successfully filed suit for violations of the Federal Advisory Committee Act, challenging its legitimacy. (NAACP Legal Defense Fund v. Barr, et al., 2020).

In Louisville, after the Louisville Metro Police Department (LMPD) used militaristic force on peaceful protestors, as they protested against police violence, LDF filed suit to challenge LMPD’s use of force. (Scott v. Louisville/Metro Government, et al., 2020)

In Philadelphia, after the Philadelphia Police Department (PPD) used militaristic force on residents in a predominantly Black neighborhood in West Philadelphia, LDF filed suit challenging the PPD’s excessive use of force. (Smith v. City of Philadelphia, et al., 2020).

In New York City, after an NYPD officer attacked a protestor, forcibly removing Mr. Smith’s mask – which he was wearing to protect himself and others from COVID-19 – and pepper-sprayed him in the face, LDF sued the City of New York. (Smith v. City of New York, 2020)

In Alamance County, North Carolina, marchers and prospective voters walking from a church to a nearby polling site—among them young children, elderly individuals, and those with disabilities— were repeatedly pepper-sprayed without warning or provocation by police. Some prospective voters were unable to register to vote by the 3 p.m. deadline and therefore could not vote on Election Day. LDF and co-counsel filed a lawsuit against the City of Graham and Alamance County challenging this unwarranted use of force and intimidation of prospective voters.

Promoting transparency and accountability in police union contracts

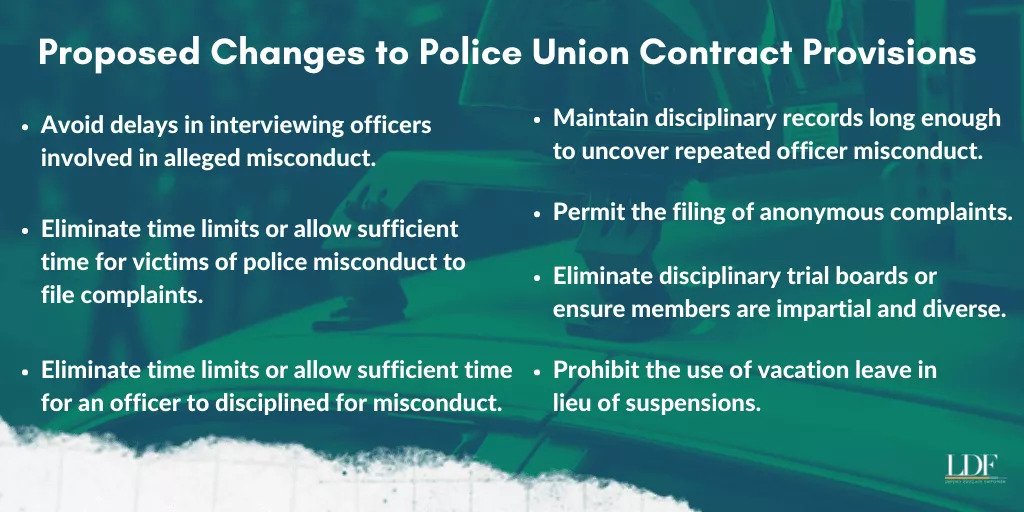

Police union contracts frequently contain provisions that shield officers from discipline and create barriers to the timely, thorough investigation of police misconduct complaints. This toolkit will help guide the public through the process of inquiring about the status of police union contracts in their localities, with the goal of promoting transparency and accountability by encouraging the removal of these provisions.

LDF’s toolkit consists of six sections that we identified as areas of concern after reviewing 112 police union contracts in 82 of the country’s largest cities. Each section describes how its designated area of concern can impede investigations of complaints or shield officers from discipline for misconduct. It also includes a list of questions that individuals can use to help them pinpoint areas where changes are needed in their locality’s police union contracts.

The six areas of concern are: (1) delays in interviewing officers accused of misconduct; (2) limits on time periods for imposing discipline on officers accused of misconduct; (3) requirements that complaints be signed or sworn; (4) removal of disciplinary records from police personnel files; (5) the use and composition of disciplinary hearing boards; and (6) the use of vacation or other leave time in lieu of suspension.